web page by Cat Berrick, 2018

Threat Levels

Benign

Healthy trees will not be adversely affected, death is unlikely even for stressed trees.

Moderate

Stressed or weakened trees are susceptible to injury or death.

Severe

Both healthy and stressed trees can die from this threat.

Dog-day cicada: BenignTAXONOMY

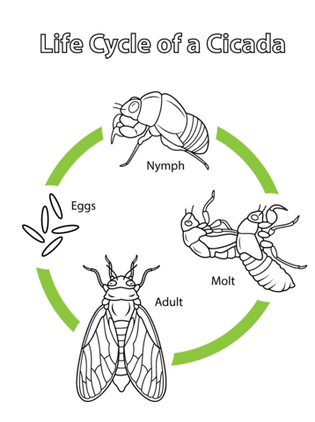

Order: Hemiptera, Suborder: Auchenorrhyncha, Infraorder: Cicadomorpha, Family: Cicadidae. ABOUT Dog-day cicadas have considerably large eyes that can be black or red, a black and green body and translucent wings, and can grow to be 2 inches in length. For healthy trees that are aren’t already weakened from another parasite or disease, cicadas are not a threat, but female oviposition sites can be detrimental to young or newly planted trees. Cicadas have an organ called the ovipositor that is used to lay eggs in bark slits, which causes splitting and can damage branches (8, 15). WHERE AM I? Cicadas are found in North America, including eastern and central states, and in parts of southern Canada (15). LIFE CYCLE

In late summer, mature nymphs emerge from the soil and attach to a tree or other surface to molt. Adult males attract females with buzzing. Within a few weeks, adults mate, lay eggs, and then die (8). SIGNS & SYMPTOMS Trees that host cicadas may have slits in the twigs, which indicate an oviposition site. Oviposition can fray or split the twig, but this is only a serious threat in very young trees (8). WHO MIGHT FEAR ME? All hardwood trees are potential hosts for cicadas, but cicadas are primarily found on oaks. Other preferred hosts include ornamental trees and trees that bear fruit (8). RESPONSE, TREATMENT & RECOVERY On small trees that have twig damage, it is crucial that the tree is monitored and pruned to prevent decreased productivity of the tree (7). Since cicadas are fairly harmless insects, treatment to host trees is unnecessary. For young trees, netting may be used to prevent female cicadas from laying eggs on small branches, or pesticide sprays can be applied (7). They may even add to the sensory experience of an urban forest, with their deafening but familiar drone during mating season. BONUS MATERIAL: Listen to my mating call here: http://songsofinsects.com/cicadas/dog-day-cicada |

Two-lined Chestnut Borer: ModerateTAXONOMY

Order: Coleoptera, Family: Buprestidae. ABOUT The two-lined chestnut borer (TLCB) attacks weakened oak trees, taking years to kill them. The harmful effects of insects like the TLCB are amplified in trees that have insufficient nutrient uptake, construction, drought, or waterlogging, which decreases tree vigor (1, 9, 10). WHERE AM I? Two-lined chestnut borers are found in southern Canada and throughout the eastern United States, including in Kansas, Nebraska, and South Dakota (9). LIFE CYCLE Two-lined chestnut borers operate on a top-down system, with adults starting at the crown of the tree and chowing down on leaves, eventually making their way to the trunk. Eggs are laid in bark cracks and upon hatching, larvae burrow through the cambium to the sapwood. Similar to the emerald ash borer, adults leave a D-shaped hole upon emergence (9). WHO MIGHT FEAR ME? TLCB hosts include all trees in the Quercus (oak) family; in Nebraska the red oak (Quercus rubra), white oak (Quercus alba), swamp white oak (Quercus bicolor), bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa) and sawtooth oak (Quercus acutissima) (9, 12). DETECTION & IMPACTS Infested oaks display defoliation and reddish discoloration as well as branch dieback. Like emerald ash borers, two-lined chestnut borer larvae leave serpentine galleries on the wood beneath the bark (9). RESPONSE, TREATMENT & RECOVERY

Heavy watering has been shown to save oak trees with a dieback of <50%. In urban settings with high-value trees that provide shade, insecticides may be applied but will not return the tree to its health pre-infestation (11). Treatment of infested oaks primarily involves ensuring that the tree is not further stressed. Watering, insecticide application, and forest thinning can reduce stress. Pruning infested branches at appropriate times may slow the spread of TLCB (19). |

Emerald Ash Borer: SevereTAXONOMY

Order: Coleoptera, Family: Buprestidae. ABOUT Emerald ash borers (EAB) are a threat to both healthy and stressed ash trees. Stressed trees can include trees that have injuries from bad pruning jobs, are suffering from other parasites or diseases, or don’t have adequate nutrient uptake. EAB attacks trees quietly and rapidly, killing their hosts in as little as two to three years (16). WHERE AM I? EAB originated in China, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, the Russian Far East but has spread to much of the eastern United States and southern Canada (16). LIFE CYCLE In the larval stage, emerald ash borers nestle up right under the bark and munch on phloem to their hearts’ content, killing the tree. Mating occurs in the spring. During the short (two to three-week) lifespan of adult emerald ash borers, a female can lay up to 90 eggs and eggs hatch in 7-10 days. Infected trees have D-shaped holes, caused by adults emerging from trees (16). WHO MIGHT FEAR ME? All ash trees in the United States are susceptible to EAB (16). DETECTION AND IMPACTS Infested ash trees will first have crown dieback since larvae start from the top and make their way down. Other symptoms include woodpecker pecks, as woodpeckers eat larvae under the bark, as well as vertical bark splintering. Larval feeding leave serpentine-like galleries in the woodgrain under the bark and these galleries will be filled with excrement and sawdust. Some ash trees will have epicormic shoots that grow from roots and trunk and possess large leaves. Once D-shaped holes can be seen, the tree is at the late stage of infestation and will die (3, 20). RESPONSE, TREATMENT & RECOVERY

Once an ash tree is infested, the tree will not survive unless insecticides are applied (16). Parasitic wasps prey on EAB larvae and can be used in some situations as a detection tool for ash trees in the early stages of infestation (2). Insecticides can be used with trees that already have crown dieback and range from yearly applications to several applications within a year (13). BONUS MATERIAL:

Watch me spread across North America here: http://www.emeraldashborer.info/timeline.php |

Literature Cited

1. Boa, Eric. 2003. An illustrated guide to the state of health of trees. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://www.fao.org/docrep/007/y5041e/y5041e06.htm

2. Careless, Philip D., Marshall, Stephen A., Gill, Bruce D., Appleton, Erin, Favrin, Robert and Kimoto, Troy. 2009. Cercis fumipennis – A Biosurveillance Tool for Emerald Ash Borer. University of Guelph. http://www.emeraldashborer.info/documents/CFIA-CercerisBook_r06.pdf

3. Hahn, Jeffery. Emerald ash borer. University of Minnesota Extension. https://www.extension.umn.edu/garden/insects/find/emerald-ash-borer/

4. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/wcm/connect/34d156ba-c9d6-4424-8b61-b80f6eb5451a/breedingcloseup_894.jpg?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=l3a4vqP&CVID=l3a4vqP&CVID=l3a4vqP&CVID=l3a4vqP&CVID=l3a4vqP&CVID=l3a4vqP&CVID=l3a4vqP

5. https://www.flickr.com/photos/mjbpics/9213084862

6. https://i.pinimg.com/originals/da/43/71/da4371a715981553d0fc2f9a808e23a2.png

7. Krawczyk, Grzegorz. Tree Fruit Production - Periodical Cicada. Penn State Extension. http://extension.psu.edu/plants/tree-fruit/insects-mites/factsheets/periodical-cicada

8. MDC. Annual Cicadas (Dog-Day Cicadas) in Missouri, cicadas in the genus Tibicen. Missouri Department of Conservation. https://nature.mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/annual-cicadas

9. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Two-Lined Chestnut Borers - Tree Care. www.dnr.state.mn.us/treecare/forest_health/tlcb/index.html.

10. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Two-lined chestnut borer. https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/treecare/forest_health/tlcb/index.html

11. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Management options. https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/treecare/forest_health/tlcb/management.html

12. Pool, Raymond J. 1966. Handbook of Nebraska Trees: A Guide to the Native and Most Important Introduced Species. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1095&context=natrespapers

13. Rebek, Kimberly A. and Smitley, David R. 2009. Homeowner Guide to Emerald Ash Borer Treatment. Pennsylvania State University, Department of Entomology. UFL. Cicada. University of Florida School of Forest Resources and Conservation. http://www.sfrc.ufl.edu/extension/4h/foresthealth/insects/cicadas.html

14. thingsbiological.wordpress.com/2011/08/26/for-ms-maxsons-class-dog-day-cicadas-tibicen-canicularis-up-close-and-personal/

15. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 2018. Emerald Ash Borer. www.aphis.usda.gov/wcm/connect/34d156ba-c9d6-44248b61b80f6eb5451a/breedingcloseup_894.jpg?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=l3a4vqP&CVID=l3a4vqP&CVID=l3a4vqP&CVID=l3a4vqP&CVID=l3a4vqP&CVID=l3a4vqP&CVID=l3a4vqP

16. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 1988. Ostry, Michael E.; Wilson, Louis R; McNabb, Harold S., Jr.; Moore, Lincoln M. A guide to insect, disease, and animal pests of poplars. Agri handbook. 677.

17. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 1985. Insects of eastern forests. Misc. Publ. 1426. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 608 p.

18. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Emerald Ash Borer. https://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/disturbance/invasive_species/eab/effects_impacts/ash_mortality/

19. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Twolined Chestnut Borer. https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5350723.pdf

20. Wilson, Mary. 2009. Symptoms and Signs of the Emerald Ash Borer. Michigan State University, Department of Entomology. http://ento.psu.edu/extension/trees-shrubs/emerald-ash-borer/factsheets/EAB2938.pdf

Cat Berrick (2018)

Contact me: [email protected]

Contact me: [email protected]